Whether you are a parent, teacher, or therapist, do you know children who would benefit from play experiences and practice performing tasks that do not come easily?

Do you ever find yourself avoiding trying something because it’s new or because you’re afraid you won’t be all that good at it? We all do. But put yourself in the place of a preschool child, or a child with a disability. I remember being in kindergarten and believing that every child in the room could draw a great heart, except for me. I remember feeling so discouraged and telling myself that I was just bad at drawing. As an adult, I realize that drawing a heart shape is not easy, and it was unreasonable for me to expect that I would be able to do it the first time I tried.

As educators, we don’t want this to happen to any child, but we know that trying and practicing things that are difficult is especially hard for young children, particularly difficult those with disabilities. Non-preferred tasks might include practicing challenging skills – e.g., stringing beads, drawing shapes, putting together a zipper, or touching or tasting a new food.

1. Put it on the schedule:

1. Put it on the schedule:

Whether you are with your child at home or teaching in a classroom, if everyone knows that first thing after lunch we are going to be drawing shapes, or whatever the non-preferred task might be, then it is just the schedule who has the power, not the adult asking for the child to

participate.

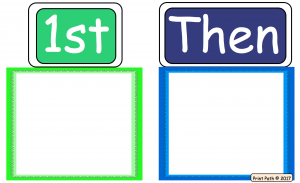

2. Make less preferred play tasks necessary before the child can participate in highly desired play tasks:

Use a clear structure. You may have limited success saying “first we are going to draw shapes and then we are going to the park.” If your child is not used to these, types of contingencies, he/she might only hear “we are going to the park” and not be able to think about anything else.

But if you add visual representations, the game changes completely. I have found “first-then” schedule cards to be extremely helpful in therapy and in the classroom for children who benefit from structure to help them participate in less desired activities.

I remember when I first used a first-then schedule with a three-year-old  boy who had autism and limited verbal communication. All he ever wanted to do was play with cars, and I needed to help him learn to pick up objects and learn new fine motor skills. I created a first-then schedule card. I put 2 blocks on the ‘first’ schedule, and as soon as he had stacked those blocks [the first time with a little help from me,] I let him play with a car for a couple minutes until my timer rang. By that time

boy who had autism and limited verbal communication. All he ever wanted to do was play with cars, and I needed to help him learn to pick up objects and learn new fine motor skills. I created a first-then schedule card. I put 2 blocks on the ‘first’ schedule, and as soon as he had stacked those blocks [the first time with a little help from me,] I let him play with a car for a couple minutes until my timer rang. By that time

I had put the two blocks back onto the ‘first’ schedule, saying that he could play with the car again as soon as he made a parking ramp and stacked those first two blocks. He learned in no time that the task was not too difficult and that he easily could do the ‘first’ task to get what he wanted. After children understand the ‘first – then’ contingency, any reasonable task can be used as the ‘first,’ and the amount of time can be expanded.

3. Use pictures:

It can be helpful to use images rather than objects to symbolize what you’re going to be doing or what’s going to be expected. Sometimes objects such as crayons or scissors, while easily understand, carry negative emotional weight for the child, are easy to push away, and likely to be rejected.

This pencil case schedule was made by Lisa, an extraordinary SL/P at our school. She was supporting a child with autism during free play, and the child would only choose two out of the 10 available stations. She put this system together by making a picture for each of the 10 play choices. If you add a 5-min timer, the child can pick any open station, but after five minutes it was time to move to another station. Then you can remove the stations already used from the available choices.

This pencil case schedule was made by Lisa, an extraordinary SL/P at our school. She was supporting a child with autism during free play, and the child would only choose two out of the 10 available stations. She put this system together by making a picture for each of the 10 play choices. If you add a 5-min timer, the child can pick any open station, but after five minutes it was time to move to another station. Then you can remove the stations already used from the available choices.

Using  this purple schedule board, I have added a bit more structure to the picture representation strategy described above. I have found this type of schedule helpful for classroom play or table tasks.

this purple schedule board, I have added a bit more structure to the picture representation strategy described above. I have found this type of schedule helpful for classroom play or table tasks.

4. Encourage a Growth Mindset:

When teaching or demonstrating a project, model the trying, the effort, and practice involved in learning the task not just how the task is done. Model an internal dialogue to support your continued attempts. When you show a mistake or an error, continue to model an internal dialogue that reflects an open mindset. For example, if you are showing children how to draw a heart, first show typical mistakes. Check to make sure your children recognize that that the heart you made did not turn out well. Then with several attempts and saying to yourself, “I start in the center, hook up, and slant down,” show improved hearts, saying, “I needed to keep on trying and then I was able to do it.”

model an internal dialogue that reflects an open mindset. For example, if you are showing children how to draw a heart, first show typical mistakes. Check to make sure your children recognize that that the heart you made did not turn out well. Then with several attempts and saying to yourself, “I start in the center, hook up, and slant down,” show improved hearts, saying, “I needed to keep on trying and then I was able to do it.”

5. Take Turns:

I am working with a 3-year-old girl who finds it difficult to try new foods. At snack time I don’t just expect her to kiss or touch the new food with her tongue, or take a bite. Instead, I take turns with her. When it is “my turn,” she gets to see me pick up a small piece of food and touch it to my lips. Once picking it up and touching it to her lips comes easy to her, I up the ante and model taking turns with touching the food to teeth or tongue.

I am working with a 3-year-old girl who finds it difficult to try new foods. At snack time I don’t just expect her to kiss or touch the new food with her tongue, or take a bite. Instead, I take turns with her. When it is “my turn,” she gets to see me pick up a small piece of food and touch it to my lips. Once picking it up and touching it to her lips comes easy to her, I up the ante and model taking turns with touching the food to teeth or tongue.

6.  Last, but not least, Make it FUN!

Last, but not least, Make it FUN!

Keep in mind, the ultimate goal is not to get the children to do what we want them to do, it is to help them gain skills and find joy in a greater variety of activities.

Techniques to encourage a reluctant child to enjoy non-preferred tasks will never work if the task is a drudge. All kids have preferences, so embed and expand upon what the child prefers into the new tasks to make them FUN! If you model enthusiasm, that emotion can be contagious, and children will naturally be interested in discovering what you are so eager about. I am woking with a child now who is fascinated with robots. In therapy we use blocks to build ‘robot towers and bridges,’ we draw ‘robot faces,’ we string beads to pretend ‘marching robots,’ and so on.

How have you used a child’s preferences to expand upon her/his activity repertoire?

![]()

Here are some of the products featured in this post.

Check out what my friends from Teacher Talk are saying!

Check out what my friends from Teacher Talk are saying!

[inlinkz_linkup id=696799 mode=1]

What a great article…! I am working with a student who has Down’s Syndrome and is 5 year old.. he is very self-directed and loves to run away from me… I actually think he likes it when people chase him… I will definitely incorporate some of these examples. It’s been a struggle… for everyone!

Your post is loaded with great tips! I love the “First, then” cards! I could use this with my sixth graders. Thank you.

You offer practical and wise advice in this post. I especially like the growth mindset approach…how we think about the task can change our approach to it. Thank you!

Your post is so insightful with so many great examples of how you can get a child to do their non-preferred tasks. You make it fun. Thanks for sharing.

The real fun is when the child starts to believe they can do ‘it’, and starts to choose whatever ‘it’ is on their own. What used to be a challenge, becomes a pleasure!